The Quiet Math Behind a Child’s First Swim Lesson

It is rarely a happy moment when parents start thinking about swim lessons. It usually comes as a shock, prompted by a pool invitation or a rental listing that mentions lake access in passing. This shifts the focus from recreation to responsibility in a way that feels immediate and intimate.

Since water is inherently unpredictable and remarkably unaffected by intention, many families view swimming as a calculation rather than a sport, weighing freedom against risk and wondering how much preparation is sufficient.

| Key Context | Details |

|---|---|

| Primary safety concern | Drowning remains a leading accidental cause of death for children ages 1–4 |

| Pediatric guidance | Swim lessons are recommended as one protective layer, not a guarantee |

| Early exposure window | Parent-child water classes often begin around 6 months |

| Formal skill readiness | Most children gain coordination for independent swimming near age 4 |

| Medical authority | American Academy of Pediatrics |

Over the past ten years, pediatric guidelines have become more clear, especially from the American Academy of Pediatrics, which presents swim lessons as one layer of protection that complements barriers, supervision, and fundamental safety practices rather than taking their place.

This discrepancy is especially helpful because it challenges the reassuring but false notion that lessons by themselves can eliminate danger. This notion occasionally creeps covertly through parent organizations seeking certainty where none actually exists.

Swim programs have responded in recent years by breaking down childhood into developmental phases. This is a very successful strategy when it conforms to the way children truly develop rather than the speed at which adults anticipate progress.

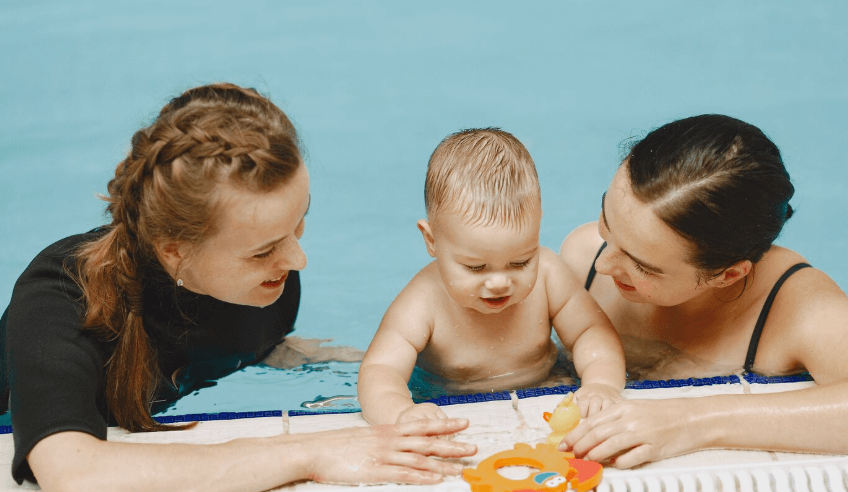

Contrary to what promotional images may indicate, infants between the ages of six and twelve months are being supported by parents who are frequently more anxious than their children as they become accustomed to buoyancy, sound, and sensation rather than learning strokes or survival skills.

These early classes, which are quietly organized and surprisingly soothing, serve more as orientation than instruction, assisting infants in coming to terms with the fact that movement in the water feels unfamiliar but safe.

With their curiosity honed by mobility and a growing sense of independence, toddlers add a new level of complexity to lessons. This makes them both more productive and more unpredictable, particularly when emotions change suddenly.

At this point, teachers concentrate on behaviors like turning toward a wall, momentarily floating, or regaining balance after falling below the surface that can be drastically reduced to muscle memory in the future.

After weeks of resistance, I once witnessed a toddler master backfloating, and the parent’s silent relief lasted longer than the cheers.

Since children can now follow instructions, coordinate their limbs, and comprehend cause and effect, formal instruction can begin to take shape in ways that feel structured rather than improvised. This shift in tone occurs around the age of four.

Since weekly lessons reinforce patterns before fear or frustration has a chance to set in, consistency often significantly improves this period. Instructors describe this rhythm as highly effective for developing both skill and trust.

However, this is also the time when fear may surface not because kids are weaker, but rather because they are suddenly able to think more clearly and recognize depth, distance, and consequence with a seriousness that may surprise adults.

When confidence falters after initial enthusiasm, developmental specialists refer to this change as awareness rather than regression. This reframing enables parents to respond with patience rather than pressure.

I recall how quickly a child’s confidence can wane after they realize what water can do.

Regardless of whether they were raised swimming regularly or avoiding the water completely, parents have a subtle but significant impact on their children’s reactions by using their body language, tone, and touch.

Teachers frequently claim that by observing how an adult enters the water, they can predict the outcome of a lesson. This serves as a reminder that assurance is conveyed physically long before it is spoken.

This environment is made more difficult by commercial messaging, as swim schools compete by offering quicker results and occasionally rely on language that sounds comforting but blurs the distinction between protection and preparation.

Here, medical advice is remarkably consistent, stressing that while early exposure can be very dependable for fostering familiarity and lowering later resistance, there is no proof that lessons taught before the age of twelve months lower the risk of drowning.

Experts contend that providing the proper conditions—such as warm water, patient instruction, and a child who is emotionally and physically prepared to participate—is more important than starting as early as possible.

Once formal skills are introduced, families frequently discover that progress accelerates considerably when lessons are matched to developmental readiness rather than calendar age.

Simple and visible indicators of practical readiness, like a child accepting water on their face, obeying simple directions, and calmingly recovering from a surprise, are frequently more important than enrollment requirements.

Regular exposure outperforms intense bursts followed by extended periods away from water, making consistency stand out as particularly innovative in its simplicity.

When timed carefully, swim lessons impart lessons that go beyond the pool. They reinforce the idea that unfamiliar situations can be learned, controlled, and eventually enjoyed—a mindset that is easily transferred into playgrounds and classrooms.

Children correcting adults about pool rules or laughing after an unexpected splash are two examples of how parents frequently observe these changes inadvertently.

Parents are reminded that progress rarely follows a straight line by the fact that children develop unevenly, families change, and environments change, so the question of when to start is never neatly resolved.

Still, it is encouraging to know that water waits patiently, providing no deadlines but rather the chance for meticulous planning, consistent exposure, and confidence developed one conscious step at a time.